Curated by Patrice Marandel, Bodies and Shadows: Caravaggio and His Legacy studies that moment in art history when artists began to break away from the carefully maintained balance of Renaissance intellectual and aesthetic traditions and take a dive into the real-life physical and emotional drama of human existence. Chiaroscuro, the dramatic interplay of light and shade, was not merely the painterly technique of juxtaposing dark and light to achieve theatrical visual effects, but also a way to explore the conflicting qualities of light and dark in the human psyche--qualities that Caravaggio came to personify in his short, chaotic life. In his case, the shadow side won out.

About the show: you stand in awe in front of paintings like "St. Francis of Assisi in Ecstasy"...

... and "Saint John the Baptist"...

It's the powerful thrust and juxtaposition of diagonals that so strongly evoke the drama of inner conflict in this artist's work. My own favorite Caravaggio, "The Martyrdom of Saint Peter"...

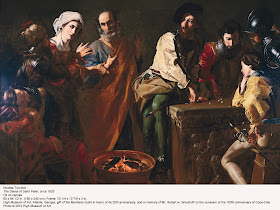

... is not included in this exhibition. I saw it years ago in Rome (Peter's city) at a time when I was going through my own inner crisis. Long-time readers will know that I bear my name because I was born on the (Anglican) Feast of St. Peter's Chains--the day that commemorates the liberation of Peter from captivity before he went on to become the first bishop of Rome; and to be crucified, upside down, for his faith. He insisted that it be upside down, the story goes, because he deemed himself unworthy of the same death as his Savior. Like the best Caravaggios, the painting captures to perfection the very real drama of Peter's very human suffering. And another painting included in the exhibition, Nicholas Tournier's "The Denial of Saint Peter"...

... reminds of the reason for the apostle's lasting self-recrimination. Peter's dark side emerged in his cowardly betrayal of Jesus at the very moment when his loyalty was needed and put to the test.

If I identify with Caravaggio's representations of this Peter, it is because I have personal experience of both his light side and his shadow. I suspect that is true for most other human beings, but it's the case particularly, for me, with Peter, for reasons whose broad outlines are obvious--we share a name, we share the experience of human suffering--and whose details I have explored in depth elsewhere and need not go into here. The point, I think, is that it's not just Peter. If we examine this artist's paintings with the same unflinching authenticity with which they are painted, with the same willingness to lay bare our souls, we will recognize ourselves in them; we will recognize the drama of our inner conflicts and the suffering they cause; and still, remarkably, we will recognize that obstinate gleam of hope that represents out better angels. We will find the glory of the flesh in all its promise of sensual ecstasy, and the agony of its susceptibility to pain and its mortality.

There are fine paintings in the rest of this ambitious exhibition--paintings by artists whose geographical origins are as widespread as Orazio Gentileschi, Georges de la Tour, Francisco de Zurburan, Gerrit van Honthorst and others. Some were clearly directly influenced by first-hand contact with Caravaggio's work, others by the more broadly distributed cultural awareness that manifests as a common thread in the work of European poets and artists of the time: the ecstatic conflation of the religious and the profane--particularly of the fleshly kind. Striving to maintain its relevance against the power of the protestant Reformation, even the Catholic church was beginning to encourage the adaptation of Bible stories and religious themes to the reality of lived experience.

The paintings in this exhibition are not all masterpieces--far from it. But that, I think, is not the point. The take-away is the unusual opportunity to immerse ourselves in a relatively brief period, when artists were preoccupied with similar themes and comparable approaches to a new understanding of what it means to be a human being, caught up in the age-old, irresolvable conflict between our better angels and the demons that torment us.

When in Rome during the late 60's I drew from Caravaggio and the Martyrdom of St Andrew by Jusepe de Ribera as well as Velázquez in Spain during the same year. and consider him to be the best next master after Caravaggio .

ReplyDeleteVelázquez's Las Meninas (1656) was an amazing tour de force of social critique and dramatic light to dark transitions and moved me to question the representation of reality in my time. I was so moved by these three masters that I was consistently ushered out of the museum each day in Rome wanting to stay just a little longer to draw more and learn.

Rubens, Jusepe de Ribera, Bernini, and Rembrandt were all deeply influenced by his pioneering work. He is really the father of modern painting.

We were sorry to have misjudged the time, Gary, and by the time we'd finished with Caravaggio it was too late to see the Kubrick show--with your contribution to the installation. Another time...

ReplyDelete