Enough with the all-too familiar story line of Vincent van

Gogh as the sun-crazed genius with those wild eyes and the fierce red beard and

hair!

That's the Hollywood version (remember Kirk Douglas?) But that this is not the only, nor even the most interesting part of the artist's story is amply demonstrated by “Van Gogh and Nature,” an important, actually thrilling current exhibition at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts. Curated by the Clark’s Richard Kendall in collaboration with van Gogh scholars Chris Stolwijk and Sjaar van Heugten, and drawing on an international variety of sources, it serves to remind us that this man, for all his suffering, was above all an artist of the highest caliber, whose eye for nature was at once keen and discerning.

We know from the letters to his brother, Theo, that—between terrible bouts of what we’d recognize today as a probably treatable psychiatric disorder—his was a highly literate, perceptive, often astutely analytical mind. This exhibition presents him as a meticulous and obsessively curious observer of the external world, a naturally skilled draftsman and gifted painter, who strove constantly, as do all true artists, to refine his vision and the mastery of his medium.

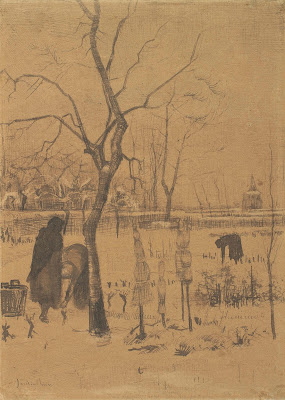

Excellently installed to facilitate viewing, and with usefully informational wall tags, the exhibition starts us off with a handful of the earliest drawings, dating from 1881 to 1883. Here...

That's the Hollywood version (remember Kirk Douglas?) But that this is not the only, nor even the most interesting part of the artist's story is amply demonstrated by “Van Gogh and Nature,” an important, actually thrilling current exhibition at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts. Curated by the Clark’s Richard Kendall in collaboration with van Gogh scholars Chris Stolwijk and Sjaar van Heugten, and drawing on an international variety of sources, it serves to remind us that this man, for all his suffering, was above all an artist of the highest caliber, whose eye for nature was at once keen and discerning.

We know from the letters to his brother, Theo, that—between terrible bouts of what we’d recognize today as a probably treatable psychiatric disorder—his was a highly literate, perceptive, often astutely analytical mind. This exhibition presents him as a meticulous and obsessively curious observer of the external world, a naturally skilled draftsman and gifted painter, who strove constantly, as do all true artists, to refine his vision and the mastery of his medium.

Excellently installed to facilitate viewing, and with usefully informational wall tags, the exhibition starts us off with a handful of the earliest drawings, dating from 1881 to 1883. Here...

... we can almost physically share the perceptual work involved in the transmission that takes place between eye and hand--looking up at the scene, looking down at the sketch pad--and the sometimes rhythmic, sometimes purely lyrical marks made by the artist's pen as he attempts to scratch out in every significant detail the quotidian drama of real-life as it unfolds before him. No madness here; yet the observing eye is compassionate, certainly, as it registers the sheer physical labor of its subjects and the poverty of their clothing in the chill of the air. We know about the young van Gogh's affinity for the poor, the destitute and the hard-working laborer, and we feel him pushing his as yet not fully developed skills to their limit, to convey his compassion in this simple sketch.

We also watch the artist's thoughtful learning process continuing after his move to Paris in 1886, as he observes, digests, and processes the work of predecessors and contemporaries in order to move his own work forward. This is the artist's way: to learn from others. An avid collector of Japanese prints from his earliest days, he sought to incorporate their aesthetic, in both style and spirit, into his own vision. In a wall devoted to his admiration for Millet (both form and content of works like "The Sower" suggest that this artist was an important, formative influence), the exhibition amply documents van Gogh's efforts to understand his mentor's visual process, and to transform it in his own language...

Van Gogh's borrowing and experimentation at this time reveal an artist working with astute critical awareness to define the particularity of his voice among those of other artists, while grounding his practice in the skills of intense observation. Here he is, in 1887, engaged in the meticulous visual rendering of a copper vase of flowers...

... as much interested in the rendering of the metallic surface of the vase as in the biological detail of the flowers and the patterned wall behind them. To emphasize the point, the curators include the very vase that van Gogh used for this painting in their exhibition, in a display case set alongside the art work. The visitor's eye wanders, as did the artist's, restlessly between the two. We are allowed to participate, in this way, in his act of observation and creation.

Flowers, of course, become a major theme in van Gogh's work; we think almost reactively when we hear his name of sunflowers and irises. But his fascination with the natural world was not limited to plant life, nor to the familiar landscapes. In smaller scale--and to me surprisingly, and with great delight--"Van Gogh and Nature" invites us to compare this study of a moth, with its attentive notation of anatomical detail...

... with this marvelous, intimate painting...

... whose tonality, coloration and varied brushwork allow the artist to evoke both the naturalistic image of flora and fauna and the magical, almost ecstatic moment of his real-life encounter with nature. Here, in this tiny image, we find distilled all the painterly skill familiar to us in his better-known paintings, while its scale draws us in to pay closer attention to the process of its making, the artist's hand at work.

While hospitalized at Saint-Rémy, van Gogh had permission to wander the grounds, where he appeared to find numerous intimate subjects to study in this way...

But his eye was also drawn to the bigger picture, the landscape beyond the hospital grounds, and here again we note not only the disturbance of his mind--and yes, the turmoil is there, almost painfully evident at the surface of the paintings--...

Van Gogh's borrowing and experimentation at this time reveal an artist working with astute critical awareness to define the particularity of his voice among those of other artists, while grounding his practice in the skills of intense observation. Here he is, in 1887, engaged in the meticulous visual rendering of a copper vase of flowers...

... as much interested in the rendering of the metallic surface of the vase as in the biological detail of the flowers and the patterned wall behind them. To emphasize the point, the curators include the very vase that van Gogh used for this painting in their exhibition, in a display case set alongside the art work. The visitor's eye wanders, as did the artist's, restlessly between the two. We are allowed to participate, in this way, in his act of observation and creation.

Flowers, of course, become a major theme in van Gogh's work; we think almost reactively when we hear his name of sunflowers and irises. But his fascination with the natural world was not limited to plant life, nor to the familiar landscapes. In smaller scale--and to me surprisingly, and with great delight--"Van Gogh and Nature" invites us to compare this study of a moth, with its attentive notation of anatomical detail...

|

| Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, 1853–1890), Giant Peacock Moth, 1889. Chalk with pen and brush and ink on paper, 16.3 x 24.2 cm. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation) |

|

| Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, 1853–1890), Giant Peacock Moth, 1889. Oil on canvas, 33.5 x 24.5 cm. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation) |

While hospitalized at Saint-Rémy, van Gogh had permission to wander the grounds, where he appeared to find numerous intimate subjects to study in this way...

|

| Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, 1853–1890), Butterflies and Poppies,1890. Oil on canvas, 35 x 25.5 cm. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation) |

5 comments:

Beautiful review Peter. Love your conclusion: " if we wish to get the most out of our art experience, to put aside the eventually frivolous distraction of a tragic life story and to come back, always, to the work."

Thanks, Gregg.

I agree with Gregg. We also hear too much about Van Gogh's emotional story and not enough about his work and this entry wonderfully reminds us of his artistic journey and how relentless he worked at his craft to become the great painter he did. He will always be one of my biggest inspirations. Thank you for this post Peter!

Thank you Peter for explaining the creative journey of this amazing artist.

Excellent- although I can never separate the man from his work (but not the popular image of him, more how he reveals his inner self through his letters.)

Post a Comment